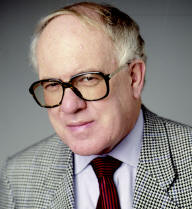

John Jenkins Feb 11

Magazine

As a publisher and editor I have been answering queries from writers for something like 20 years and as a result I have recently published a book FAQs and the Answers for Ambitious Writers.

As a publisher and editor I have been answering queries from writers for something like 20 years and as a result I have recently published a book FAQs and the Answers for Ambitious Writers.

Why How good are you at creating characters?

by John Jenkins

It’s one thing to remember great characters from what you read – but quite another to create them. Like all writing tasks begin simply and work up from there.

Start by writing about "your most memorable character." Then re-write the same material, adding, emphasising – turning homo sapiens into homo fictus because the main character in a book always appears larger than life.

He is more handsome, tougher, weaker, meaner, uglier, nobler, vengeful, braver or cowardly than the man next door. But he is not a caricature.

You have to create him. You play god. There are three things to remember as you set up your creation. Lajon Egri, in his book, The Art of Dramatic Writing, insists on these aspects to create a well rounded character: The first is the easiest: physiological dimensions and appearance.

The second is sociological

and the third psychological.

Age - sex - height - race - health - nationality. Ian Botham would not have been a super star if he had been born with a withered right arm. Marilyn Monroe would not have been the star she was if she had been flat-chested, Colin Firth would not have been an actor if he really stuttered. Physical traits frequently have a bearing on character. Think of Cyrano de Bergerac and Long John Silver. Think of Richard Burton’s voice and Barbra Streisand’s voice.

Thin or fat, tall or short beautiful or ugly – these traits can help to delineate your character at a glance. Clothes can be important.

Have you employed all the senses: sight, touch, smell, taste, sound and remember the sixth sense, so useful for crime writers.

Now we get to that favourite British topic: class. The sociological boundaries which help to shape a person. Where did he grow up, what was his education, which church did he attend, his political views, attitudes on sex, race and money? Does he mix easily and make friends, is he a loner? Character is frequently forged by the sociological climate in which the person develops.

Psychological traits are often the most interesting: fears and manias, IQ rating, complexes, habits, inhibitions. You do not need to have read Jung or Freud to practise as an amateur psychologist. What makes a hero? What makes a psychopath?

Remember your character will be all the more interesting if they go against the trend in some odd way.

You need to know much more about your characters (for a book) than perhaps you need to use. This background biography which you write in your own notes for a novel will ensure that you draw people who are easy to recognise and easy for the reader to empathise with.

Why are readers captivated by so many different types of detective, from Miss Marple to Rebus, Sherlock Homes to Marlow, Barnaby to Columbo, Sam Spade to Poirot? It’s worth analysing to see what you can deduce.

Try creating a cv for them (in other words a back story).

Or try interviewing them: work out 20 questions for James Bond in order that the answers can give you deep clues to his character.

Stop and think of all the great books which you have enjoyed. Think of all the films which you remember fondly. The chances are that you remember them fundamentally for the principal character involved.

There are exceptions. You may well remember the Shawshank Redemption for three characters.

But building memorable characters is the joy of being a writer. It’s where you use your imagination. It’s where you create people who are larger than life.

I go back to my often repeated view: could a director making a film of your story cast it without talking to you?

Does a main character immediately bring to mind a star actor or actress?

Turn the problem around. Cast it before you write the story. Think of those great character actors: Peter Poslethwaite, Thora Hird, Charles Laughton, Olivier, Gielgud and Richardson.

Think of David Jason in such contrasting roles as Inspector Frost, Pa Larkin and Del Boy. Think of de Niro ‘s Jake la Motta in Raging Bull and Casino. Think of Gene Hackman in Mississippi Burning and as Popeye Doyle in the French Connection.

Take the great roles played by Helen Mirren and Judi Dench. Martin Shaw in The Professionals and as Judge John Deed. Could anybody better Basil Rathbone as Sherlock Holmes or Anthony Andrews as the Scarlet Pimpernel or Sebastian Flyte in Brideshead Revisited?

It is true to say that characters drive a story – and often characters will take it over and do the writer’s job.

All you have to do is play god. And prompt them with questions such as: Supposing this happened? Supposing that plan did not work out? Nobody can teach you imagination.

But here’s a few guidelines to help you:

-

Keep to a minimum all situations where one character appears alone. Single character scenes often lack tension or conflict. They lead to such passive conditions as soliloquies, flashbacks, speculation and author intrusion.

- Note that I did not say NEVER on this occasion for there is always the example to prove the rule wrong. Shakespeare often did it and Jack London in his masterpiece, To Build a Fire had only one character – and his dog.

- Back to films. Think in terms of scenes. Even in a short story or limited timespan you should still be able to see the characters. Ideally each scene should suggest the next turn of events. Take the opportunity to reveal another facet of your protagonist.

- Scenes are often an exchange of power or influence between two characters. This happens all the time in crime stories. First the bad guys have the upper hand, then the cops, then it is reversed etc. Your protagonist will want something which others will prevent him from achieving until… that is the story.

- Protagonists and antagonists become more interesting as they become larger than life. They are going to do things which you probably would not. Steal somebody’s girl, rob a bank, shoot a policeman. In Les Miserables- even the musical - the force of the story is the pursuit of Jean Valjean by Inspector Javert.

- Beware of making your characters too perfect. What would Cyrano be without his nose? Dr House without his limp? Rainman without his tic? Morse’s inability to forge a relationship with a woman? We empathise with flawed heroes.

- And do not kiss off your minor characters. Your main man must have a worthy opponent. With such a super hero as James Bond the villains must be - and are - exceptional. Remember that somebody has to get the Oscar for the best supporting actor.

John Jenkins' January column dealt with the important topic - Why a good tutor is a psychologist.

If you have a question you would like John to answer please email it to:

John@jayjay1.demon.co.uk

The latest book from John Jenkins is FAQs and the Answers for Ambitious Writers

an absurd and uninteresting fantasy which was rubbish and dull.

Related Items in our Amazon Store

|

Publisher: Cooper Johnson Limited

Kindle Edition

Sales rank: 1,480,471

|